After moving to Vancouver in 2012 I occasionally saw references in local media to something called the “Salish Sea”. I thought it must be an obscure body of water somewhere up the coast.

Finally I bothered to look it up, and it turned out the Salish Sea was the new name for what I grew up calling the Strait of Georgia. Or rather, as the inventor of the name explains, the Salish Sea encompasses the Strait of Georgia along with other adjacent bodies of water:

[T]he ecosystem science … showed clearly that the inland marine waters of Washington State along with the inland marine waters of British Columbia formed a single integrated estuarine ecosystem.

Salish Sea boundaries and watershed. Map by Kris Symer, Puget Sound Institute.

Though some are under the impression that it predates European contact, the word “Salish” has no connection to the area – it comes from a Montana tribe whose name was borrowed by linguists to describe their whole language family. The term “Salish Sea” dates only to the 1980s, and didn’t come into widespread use until the 2000s, when some aboriginal groups began lobbying for its adoption. In 2009 the name was officially accepted by the Geographical Names Board of Canada, and it was swiftly taken up by politicians, academics, and the media.

I generally disapprove of changing names for ideological reasons – for instance, because some hero of the past has fallen out of political favour. However, I do approve of changing names for reasons of clarity.

The Strait of Georgia was named after King George III. The year was 1792, and Captain George Vancouver had just arrived in the Pacific Northwest after surveying the coast of Australia, where he’d already left behind a King George Sound. Needless to say, King George never set foot in either corner of his domains.

There was nothing to prevent Captain Vancouver from coming up with a more distinctive name for the strait. There were any number of geographical features along the coast which had already been given ear-catching names by their native inhabitants, which he might have adapted to the purpose. But thinking up memorable, non-sycophantic names wasn’t how he got to be captain.

So I don’t think demoting the name Strait of Georgia is a great loss. But it’s confusing that the part of the Salish Sea that most resembles a sea – the broad part between Vancouver Island and the mainland – is still known officially as the Strait of Georgia; and that while the sea includes all the narrow appendages of Puget Sound to the south, for whatever reason it includes only some of the narrow appendages to the north.

Also I see that on Google Maps, the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound are still prominently shown, while the new name has taken the place of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

So, as often happens, the result of the new name has been to increase confusion. Wikipedia links to a 2019 survey showing that only 9% of Washingtonians and 15% of British Columbians, when shown the body of water on a map, could correctly name it.

***

Lately I get most of my international news from the Daily Mail. Don’t judge me. When I get too irritated by the idiocy of the headlines I can always cast my eye over to the sidebar and take in some starlet modelling her signature swimsuit line.

I’m not very invested in the dramas of the British royal family, but I couldn’t help being annoyed, during the “Megxit” perturbations that dominated headlines earlier in the year, at the way Daily Mail writers kept referring to the “Vancouver” mansion where Harry and Meghan holed up during their retreat from their royal duties.

The mansion in question is actually located on Vancouver Island, a 90-minute ferry ride from Vancouver.

Meghan Markle in Horth Hill Regional Park, Vancouver Island, January, 2020. Source: Daily Mail.

This lack of precision is extremely irritating to British Columbians, just as it must be irritating to upstate New Yorkers when outsiders assume they live in the vicinity of Manhattan, or to Welshmen when outsiders refer generically to the UK as “England”.

But in all these cases the errors are understandable. Who would predict that Vancouver would not be on Vancouver Island?

Captain Vancouver has done pretty well for himself. He’s remembered by a big island, a world-famous city, a less famous city, a peninsula (in Australia’s King George Sound), a couple mountains, and numerous statues and monuments.

Unlike King George and some of the other bigwigs celebrated in BC place names – Queen Victoria, Prince Rupert, Prince George, and, oh yeah, Christopher Columbus – Vancouver actually visited most of the places named for him.

I have no wish to take anything away from his legacy. And yet I feel that he can afford to lose a Wiki page or two in the interest of reducing geographical misunderstandings.

The city of Vancouver wasn’t called that until 1886, when it was chosen as the terminus for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Previously, when residents of the British Empire referred to “Vancouver” it was assumed they were talking about the island, which had been known by that name for half a century.

So in fairness the island ought to keep the name, and the city to come up with a more original one. But realistically I think if either is going to change, it must be the island. It would be different if there were many small islands off the BC coast, all of roughly equal size, one of them known as Vancouver. In that case people would be used to calling it by its full name to distinguish it from the rest.

But in fact there’s one big island, which most British Columbians refer to as “the Island”. Even residents of the smaller islands, Pender and Saltspring and Mayne and so forth, will say, “I’m headed over to the Island for the afternoon”.

So as with the Strait of Georgia, Vancouver Island can be renamed without creating too much friction in ordinary conversations. The downside is that precisely because the name doesn’t come up every day, it would take a while for people to get used to the change.

***

I wouldn’t be thinking about this at all except that – speaking of confusing names – I’ve been trying to familiarize myself with the various First Nations along the BC coast.

There are a lot of them, and it’s not always clear whether we’re talking about a single community, like the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, population 257; or an entire culture, like the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, population 3,500, comprising six band governments and dozens of reserves.

Additionally, many of them have changed their names – like the Wet’suwet’en First Nation, which used to be called the Broman Lake Band; or adopted more “authentic” versions, like the Kwakwaka’wakw, who used to go by the less tongue-punishing Kwakiutl.

It was while reading up on the Kwakiutl and their near neighbours the Nootka – sorry, the Nuu-chah-nulth – that I learned about a name that appeared on some old maps of the Pacific Northwest: the Wakash Nation. [1]

The Wakash Nation shown on 1840 Oregon Territory map. Image source: Walmart.com.

The Wakash name was bestowed by Captain James Cook during his 1778 encounter with the people of what we now call Nootka Sound (which, of course, Cook called King George’s Sound):

Were I to affix a name to the people of Nootka, as a distinct nation, I would call them Wakashians; from the word wakash, which was very frequently in their mouths. It seemed to express applause, approbation and friendship. For when they appeared to be satisfied, or well pleased with any thing they saw, or any incident that happened, they would, with one voice, call out wakash! wakash!

As it happened, the name Nootka, from a phrase meaning “sail around” – as in, “Come park your boats over here, strangers” – was extended from the village to the entire culture. But in the early years, Cook’s suggestion was followed: the Wakash Nation appeared on maps well into the 19th century, and Wakashan was eventually adapted as the name of the family to which the Nootka and Kwakiutl languages belonged.

Wakash Island strikes me as a pretty good name. I’m not sure if any of the native peoples of the region had a word that referred to the entirety of what we call Vancouver Island; but even if they did, there were two major language families and at least a dozen different dialects there. Rather than privilege one over the others, it would be fairer to use a hybrid word that emerged through cross-cultural interaction.

Those who recall their Heritage Minutes will recall that the name “Canada” came about in a similar way:

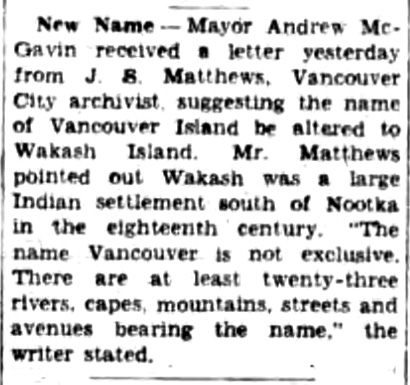

There are a few hits if you search for “Wakash Island”, including this letter to the mayor of Victoria reported by the Daily Colonist in 1943:

Vancouver archivist J.S. Matthews proposes a name change. From the Daily Colonist, February 21, 1943.

The letter writer wasn’t some random crank – that’s Major James Skitt Matthews, founder and longtime head of the Vancouver Archives. (Nor was he some soppy liberal seeking to make amends for Canada’s imperialist past: “a staunch patriot, he once fell out of his chair with rage upon glimpsing Canada’s new maple leaf flag”.) [2]

The only trouble with Wakash is that I’m not sure how to say it. I’m guessing “WAH-kawsh” – but the Catholic Encyclopedia offers the variant spellings wakesh and waukash, which makes me uncertain.

The danger is that some influential person suggests Vancouver Island be renamed Wakash Island, all the nice white people nod and say, “Yup, sounds good to me,” and then some indignant First Nations activist jumps up and declares that if we’re going to use a Nuu-chah-nulth word we have to use a Nuu-chah-nulth spelling, with two apostrophes, three diacritics, and a number 7 in the middle. Of course all the nice white people are too scared to say no, and we wind up with a name no-one can spell or pronounce, and more confusion than ever.

Maybe it’s safer to stick with Vancouver Island.

M.

1. Many of these old maps place the Wakash Nation on “Quadra and Vancouver’s Island”. Poor Quadra’s name would soon be dropped, but as David Paget points out, it’s still linked with Captain Vancouver’s in the name of a federal electoral district – appropriately, as the two captains’ relationship was built on diplomatic haggling over ownership of the coast.

2. It doesn’t really matter how Wakash is pronounced, as long as everyone agrees about it. Looking up archivist J.S. Matthews I came across this anecdote from the poet John Pass, who worked briefly with the elderly Major in the late 1960s:

I liked hearing him fulminate, for example, on the universal mispronunciation of Burrard, that the man for whom the street was named would be livid to hear us put the accent on the last syllable, Burrard. It was Burrard.

—

My previous post on the “rectification of names” touched on Chinese characters, the “Wuhan flu”, and The Neverending Story. I’m a big fan of the City of Vancouver’s online archive, which I consulted for a post last year on abandoned rapid transit plans and which was the source of many of the out-of-copyright film clips used in this music video.

0 Responses to “The rectification of names: Wakash Island.”