My recent interest in the Chinese language was sparked by the appearance last spring of an unusual volume of news reports out of China. At that time I realized to my vexation that I knew almost nothing about Chinese geography.

I’d at least heard of Wuhan. It gets a few paragraphs in Paul Theroux’s 1988 travel book Riding the Iron Rooster. He’d visited there years before and remembered it as “a nightmare city of muddy streets and black factories, pouring frothy poisons into the Yangtze”. By his second visit it had cleaned up and sprouted new towers, but its lurches into modernity, Theroux grumbled, “were not necessarily improvements”.

I learn from Wikipedia that Wuhan played a major role in 20th century Chinese history, as the seat of the 1911 rebellion that ended the Qing Dynasty and brought Sun Yat-sen’s Kuomintang to power. The septuagenarian Mao Zedong’s famous exhibition of his vitality – swimming 15 kilometres in the Yangtze River (with the assistance of the current) – took place at Wuhan in 1966.

Nowadays metropolitan Wuhan has almost 10 million people, about the same as Chicago. And up until last year, I couldn’t have told you even roughly where it was.

Embarrassed by my ignorance, I began looking at maps of China. As some of those maps included the Chinese names for cities and other geographical features, I began to notice the recurrence of certain characters: the hai in Shanghai and Hainan; the an in Anhui and Xi’an; the bei in Beijing, Hubei, and…Taipei?

On the other hand, the jiang in Xinjiang was not to be confused with the one in Jiangsu and Heilongjiang.

Intrigued, I began drawing a map, labelling it in English and Chinese, looking up the meaning of the characters as I went.

Most Chinese placenames, I learned, are surprisingly straightforward. The provinces of Shandong and Shanxi are, respectively, “mountain east” and “mountain west”. Shanghai is “upon the sea”. Beijing is “northern capital”. (The kanji characters for Tokyo, “eastern capital”, are in Mandarin pronounced Dongjing.)

It didn’t take me long to learn the dozen or so characters that reappear again and again in Chinese placenames – words like river, lake, sea, mountains, forest, and the four cardinal directions.

As a strategy for actually learning Chinese, my map studies weren’t that effective. Suppose you were a foreigner trying to learn English from the names of English towns. You’d learn a handful of useful geographical words like the ones above, a few of limited everyday utility like “ford” and “shire”, and a bunch more that are fossils of long-extinct words, like “wich” and “caster”.

Nevertheless, my efforts weren’t entirely wasted. Most Chinese characters are built out of smaller pieces, most of which started as simple pictograms – a hand, a tree, an elephant, and so on.

Once you start to recognize these smaller pieces and their variant forms, the characters become less baffling – you can discern order in what appears at first glance to be a pile of squiggles.

***

I try to be explicit, whenever anyone asks: I’m not “learning Chinese”. As I explained in a post early last year, I was daunted by the prospect of absorbing a new vocabulary and grammar, plus a new writing system, plus the “tones” without which (we are told) any attempt at enunciating their language will be met with puzzlement or laughter from Chinese-speakers.

I wondered instead whether I could break out the most immediately useful of the above challenges, learning the meaning of the characters alone, with the goal of being able to decipher the signs on local Chinese storefronts.

Like most westerners, I had a vague idea that Chinese writing is purely pictographic – that it conveys sense only, not sound. This isn’t really true. Many characters are pictograms – simplified pictures of things. Others are ideograms – graphical representations of concepts. Anthony Burgess in his 1992 book on language, A Mouthful of Air, described the character 不, or “not”, as

a sort of plant with a line above it. The plant is trying to grow, but the line is stopping it. This is a little poem of negativeness, a metaphor of notness.

Still other characters are ideogrammic compounds – two or more ideograms combined to illustrate a concept. Take 意, which means “idea”.

On top is the character meaning “sound”: it depicts some mysterious force emitting from an open mouth (with a horizontal line in the mouth, just in case you’re unclear on the source of the phenomenon). Beneath it is the character for “heart”. An idea, then, is a “heart-sound”.

You don’t need to speak Chinese to absorb the meaning of characters like “not” or “idea”. If the ancient scribes had stuck to pictograms, ideograms, and ideogrammic compounds, written Chinese might have evolved into a truly universal language – something like what the 20th-century inventor Charles Bliss had in mind with his quirky system of Blissymbolics. (Which was inspired by his own experiments in self-taught Chinese.)

But despite the ingenuity of the ancient scribes, it was impractical to compose a little visual poem for every word. To make headway, they devised another, more efficient method of invention – mashing together two existing characters, one to define the broad sense of the new character, and another to suggest how it should be pronounced. These so-called phono-semantic compounds now constitute the bulk of the Chinese character set.

Here’s one. On the left side is the “foot” character, indicating that the compound will have something to do with feet. (The semantic component is usually, but by no means always, on the left.) On the right side is the character bao, meaning “to roll up”. (Yes, it also refers to the steamed bun.)

The bao part is semantically irrelevant – 跑 in fact means “to run”. But the Chinese-speaker will guess, correctly, that it should be pronounced something like bao: in Mandarin, pao.

Because at this point I’m not trying to learn to speak Chinese, these phonetic components aren’t very useful to me. I usually don’t bother trying to remember how the characters are pronounced – aside from those whose pronunciations are mnemonically useful. For instance, 糖, which combines the semantic component “rice” with the phonetic component for the Tang Dynasty.

The syllable tang naturally makes me think of astronauts and orange-flavoured juice crystals, and from there it’s a short leap to the meaning of “sugar”.

Luckily, it’s rarely necessary to smuggle in English words to make sense of phono-semantic compounds. The ancient scribes weren’t completely indifferent to the poetic reading of their new character mashups. Take 晚, or “night”. The semantic component is “sun” and the phonetic component means “to remove”.

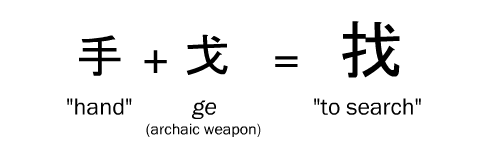

Even where the phonetic component was chosen solely for its sound, it’s usually possible to construct a little mnemonic story to help cement the compound in your mind. A well-known example is 找, “to search”, which joins the semantic “hand” with a phonetic component representing a ge, or dagger-axe: just picture a hand grasping in the dark for a weapon.

I was always being stumped by the rather impenetrable glyph 用, meaning “to use”…until I realized that the same shape, with a little handle on top, is the phonetic component of “bucket”: a “use”-ful item.

I should reiterate that the phonetic components are only hints to pronunciation. Since the characters are so old, and the spoken language has drifted so much over the millennia, many of these hints are completely misleading. Which brings me to…

An aside about Japanese.

Prior to writing this essay, I hadn’t given any thought to how the Japanese pronounce the kanji that make up around half of their writing system. (Kanji, by the way, just means “Han characters”. The Chinese call them hanzi.)

I suppose I assumed they were reading the characters for semantics only, just as I have been; that when they spoke the words aloud, they were using “native” Japanese words; and that the Chinese phonetic clues were therefore just as irrelevant to them as they are to me.

Leave it to the Japanese to do things in the most complicated possible way. It turns out that nearly every kanji has at least two readings – one for its original Chinese pronunciation and another for its “native” Japanese equivalent.

Suppose that every English word based on a Greek root was not only spelled using the Greek alphabet, but could be read either as Greek or as an equivalent term derived from Old English: “psychology”, say, would be spelled ψυχολογία and could be pronounced either as “psychologia” or as “soul-learning”. That’s sort of how the Japanese have elected to treat their Chinese loanwords.

For a foreigner trying to learn Japanese, these multiple readings must be awfully frustrating. But native Japanese learners don’t need to memorize the various readings from textbooks or flashcards – they pick them up effortlessly through speaking and listening. The kanji merely bundle together, under one symbol, various words they already know.

Perhaps the Japanese are onto something. Why not have a single symbol to represent two or more English words with the same meaning – “sight” and “vision”, for instance? Something like…oh, I dunno, 視, maybe. If nothing else, it would save space – and one of the main arguments for kanji seems to be its efficiency.

Still, it’s hard to blame the Japanese girl in this video who says of kanji, “I don’t want to learn them anymore. We can just use hiragana.”

The trouble with simplified Chinese.

As you may be aware, there are two main varieties of Chinese characters: the traditional ones, nowadays used mainly in Hong Kong and Taiwan, and the simplified ones used in mainland China. Up till now I’ve been showing the traditional characters in this essay.

The simplified characters were introduced in the 1950s, not long after the Communists took over. Around the same time, the Japanese introduced their own, less comprehensive kanji simplification scheme. Many characters simplified by the Communists kept their traditional forms in Japan. Others were simplified in a slightly different way.

Most of the characters are the same in all three writing systems. But a few, including many of the most common ones, have two, sometimes three different forms.

Here in Vancouver you mostly see the traditional characters. But the simplified versions have gained ground as immigration from mainland China has increased.

When I started dabbling in Chinese I figured I’d stick to the simplified characters because, well, they were simpler. Then as I started being able to recognize the characters on storefront signs I realized that if I ever wanted to be able to read anything around here, I should learn both varieties.

SkyTrain and Chinese language signs, Richmond, BC.

© Steve Bosch / Vancouver Sun.

Then I discovered something surprising. The traditional characters were easier to learn.

***

Let me talk about nostrils for a second. The word “nostril” comes from the Old English word “nosthyrl”. The “nos” part means “nose”. “Thyrl” is an extinct word meaning “hole”. (It’s related to the word “through”.)

So a nostril is just a nose-hole. Makes sense. But for English learners it must be pretty confusing. Why “nos” instead of “nose”? What the heck is a “tril”?

I imagine English learners must memorize “nostril” the way I’ve been memorizing Chinese characters – by way of mnemonics. Maybe something like this: a “trill” is a high-pitched sound, like you make when you whistle through your nose: a “nose-trill”.

Now, suppose that in the wake of a future Communist revolution, our new government were to decree, “Henceforth, in the name of simplicity, nostrils will be called nose-holes.” This would be sensible enough. Immigrants and schoolchildren would happily adopt the new word. In fifty years or so, after most of us old-timers had died off, “nostril” would be as extinct as “thyrl”. Good riddance!

But most linguistic reformers have less totalitarian aims. Knowing that it’s difficult to change the spoken language by decree, and that it tends to make old-timers grumpy, they concentrate on tinkering with the written language.

So the Peeple’s Kommittee Too Standerdize Inglish probably wouldn’t abolish “nostril”. They’d just change its spelling to “nawstrel”, to conform with “jaw” and “law” and “raw”.

“Nose”, obviously, would become “noze”.

And future English learners would lose a vital clue to the relationship between the two words.

***

Looking at many Chinese characters, it’s easy to see why you’d want to simplify them. Have a squint at the traditional character for “medicine” or “medical”: 醫. Unless your browser is set to an unusually large font size, it looks like a squashed bug. Here it is, magnified:

Now you can see that it includes the “arrow” character, which is easy to remember because it looks like a guy with an arrow through his head. The bottom rectangle comes from the “liquor” character, because how do you treat a guy with an arrow in his head? Obviously, with booze.

The shu at top right unnecessarily complicates my mnemonic story. Did my imaginary arrow victim also get stabbed with an antique spear?

Lucky for me, the bureaucrats who overhauled the writing system in the 1950s agreed that the shu didn’t fit: the simplified (also Japanese) character for “medicine” is just an arrow in a box. In this mnemonic story, the guy got shot with an arrow and now he’s lying on a bed in a modern, uncluttered medical facility. (Wishing he had some liquor, no doubt.)

Okay! Good job, simplifiers. But let’s look at another traditional character, 長, which means “long” – as in Chang Jiang, the “Long River”, known to us as the Yangtze.

The strokes on the bottom appear kind of random, but actually they’re a standard stroke-shape that shows up in other common characters, like the ones for “clothing” and “to eat”. The three horizontal strokes at the top are from a character meaning “hair” – because 長 originally referred to long hair.

Not too busy. Easy to remember. The Japanese simplifiers had enough sense to leave this character alone. But the mainland Chinese turned it into this:

Much quicker to draw, true: it requires half as many pen-strokes. But now the top part is missing the three horizontal lines that clue you in to its meaning, while the bottom part no longer matches the “clothing” and “to eat” characters – which weren’t simplified.

The new character is nothing but an abstract shape which must be drilled and memorized, without reference to other shapes already learned – just as westerners must learn the abstract shapes A through Z. But we have only 52 such shapes (counting lower- and upper-case) to worry about.

Did simplification make Chinese characters easier for schoolkids to learn? Having fewer strokes to memorize seems like it would be a plus, but I’d argue that the elimination of visual cues for mnemonic association cancels out the advantage. That’s been my own experience, anyway, and it’s why I’ve switched to concentrating on the traditional characters in my own haphazard studies.

***

Have I gained anything by my self-directed Chinese studies? Not much. After more than six months of, admittedly, not very conscientious efforts, I still can’t read a primary-level Chinese text. I recognize many, sometimes most of the characters, but they remain stubbornly isolated from one another. I translate each one to its likeliest English equivalent and glare suspiciously at the resulting string of nonsense.

Imagine a foreigner tackling a simple English sentence: “I am going to the state fair.” The sentence begins straightforwardly enough. But where is the speaker going? What’s this “state fair”? A condition of beauty? An administrative district of moderation? A spoken-word exhibition?

Knowing the meaning of all the words isn’t enough. Knowing all the meanings of all the words may actually add to your confusion. You need to know the most plausible ways for the words to pair up.

(And obviously, when it comes to Chinese, I’m nowhere near knowing all the meanings of all the words.)

If I’d followed a curriculum I’d likely be a little further along. On the other hand, going my own way has allowed me to skip some of the off-putting stuff – like the tones – that might have caused me to dump the project entirely.

Perhaps once I’ve achieved fluency in reading Chinese – which at my current rate of progress could easily take a decade or more – I’ll try learning to speak it as well. But probably not. I’m not that enthusiastic about conversing in Chinese. I can barely be bothered to converse in English.

M.

—

My last attempt to explicate the Chinese writing system roped together an essay by Hillaire Belloc, a novel by Robert Graves, and the elephant of Han Fei. Nine years ago I took issue with Paul Theroux’s interpretation of the American bombing of Hanoi. It seems I’ve never mentioned Anthony Burgess before – except in a footnote to last month’s essay on Robert Heinlein’s The Puppet Masters.