Part III of The Immigration Heresies.

This was written sometime in mid-2016, then shelved. I’m publishing it now as part of my Decennial Fridge-Cleaning series.

—

It often helps me get started when I have someone else’s ideas to bounce off. By luck, this morning I plucked at random a book off my shelf that touches on a theme I’ve been struggling to define.

It was Lionel Trilling’s collection The Liberal Imagination. In an essay from 1947 entitled “Manners, Morals, and the Novel”, Trilling wonders why American novelists seem to “have a kind of resistance to looking closely at society” – by which he means the existence of social classes. He writes:

Consider that Henry James is, among a large part of our reading public, still held to be at fault for noticing society as much as he did. Consider the conversation that has, for some interesting reason, become a part of our literary folklore. Scott Fitzgerald said to Ernest Hemingway, “The very rich are different from us.” Hemingway replied, “Yes, they have more money.” I have seen the exchange quoted many times and always with the intention of suggesting that Fitzgerald was infatuated by wealth and had received a salutary rebuke from his democratic friend. But the truth is that after a certain point quantity of money does indeed change into quality of personality: in an important sense the very rich are different from us. So are the very powerful, the very gifted, the very poor. Fitzgerald was right…

Earlier American writers, says Trilling, had proposed explanations for this blind spot in the national literary imagination:

There is a famous page in James’s life of Hawthorne in which James enumerates the things which are lacking to give the American novel the thick social texture of the English novel – no state; barely a specific national name; no sovereign; no court; no aristocracy…

In consequence, these writers argued, American culture offered

no sufficiency of means for the display of a variety of manners, no opportunity for the novelist to do his job of searching out reality, not enough complication of appearance to make the job interesting. Another great American novelist of very different temperament had said much the same thing some decades before: James Fenimore Cooper found that American manners were too simple and dull to nourish the novelist.

Trilling observes however that

life in America has increasingly thickened since [Henry James’s time]. It has not, to be sure, thickened so much as to permit our undergraduates to understand the characters of Balzac, to understand, that is, life in a crowded country where the competitive pressures are great, forcing intense passions to express themselves fiercely and yet within the limitations set by a strong and complicated tradition of manners. Still, life here has become more complex and more pressing.

Seventy years on, America has become much more crowded, its competitive pressures greater, its social rules more complex, in a way that, if Trilling was right, should have led to an improvement in the quality of American literature. But would anyone say the American novel circa 2017 is in better shape than it was in Trilling’s time? I doubt it. But perhaps that’s because Americans’ creative energies have shifted to other media, with movies and TV shows jostling for room at the pinnacle of the culture where novels once lorded it alone.

***

But what interests me is the phase transition alluded to by Fitzgerald in his comment about the rich, and by Trilling when he contrasts the easy manners of 19th century New England with those in “a crowded country where the competitive pressures are great”, like France or England.

In chemistry, matter undergoes a phase transition when heat is added – ice turns to water, water turns to water vapour – and that just about exhausts my knowledge of chemistry. In the social realm, phase transitions are fuzzier and harder to define, but no less real and important.

If Fitzgerald was correct that the rich really are different from us, the phase transition might occur at the point one has accumulated enough wealth to no longer have to worry about money. This gives one a certain immunity to caring what the rest of us think. Society might still condemn your nonconforming behaviour, but there’s no risk of it getting you fired.

There must be a corresponding phase transition at the bottom of the economic scale, between those with barely anything – who are desperate to preserve what little they have – and those with nothing – who have no further reason to give a damn.

Another obvious social phase transition occurs when population is added. When two individuals are brought together, social interactions that were previously nonexistent suddenly become possible. When a third person is added, the possibility of allegiances is introduced – two of the three might team up against the third. Another phase transition occurs when the group grows large enough that comfortable face-to-face conversation is no longer possible, and it splits into subgroups.

At this point we’re moving beyond the size of a family unit or social gathering and into the realm of what we would call society. The next major limit is marked by Dunbar’s number, with a phase transition occurring when the population grows beyond the number of personal relationships that the human brain is capable of managing – 150 or so, according to Robin Dunbar.

To elaborate on my highly scientific analogy, just as the boiling and freezing point of water vary according to atmospheric pressure, social phase transitions are sensitive to other pressures besides simple population growth. For instance, the Malthusian limit – the point at which a society outstrips its available food supply – varies depending on location, climate, and level of technology. Given enough agricultural, transportational, and organizational know-how to keep its population fed, a society can go on cramming in people, probably not forever, but at least until some as-yet unencountered phase transition is reached – like the “behavioural sink” brought on by overcrowding that doomed the colonies in the NIMH mouse utopia experiments.

***

Imagine a newly-arrived immigrant family in a small town in the Canadian prairies circa 1910. Wishing to preserve their ancestral customs, whatever those customs might be – Ukrainian, German, Chinese, it doesn’t matter – they reach out to nearby families of the same background with whom they can gather on traditional holidays to chat in their native language, sing their native songs, share their native recipes. But those other families live a long, rattling buggy-ride away. Between holidays our newcomers eagerly scan the international news for rare mentions of their homeland. They wait weeks for replies to their letters home. Once in a while a parcel arrives with precious canned goods unavailable in Canada, wrapped in a weeks-old newspaper. They nurture a slim hope of someday saving enough to make a trip to their home country, knowing that in all likelihood they’ll never see it again.

At work, by necessity, they speak only English. Their children attend school and make friends with Canadian-born kids who are at best politely bemused by the newcomers’ quaint customs. Within a year or two the children, now speaking unaccented English, are mildly embarrassed by their parents’ devotion to the old ways. The children switch easily between English at school and their ancestral language at home, but as they reach adulthood and move out, marry native English-speakers, see their parents less often, their sense of ethnic identity fades. The next generation picks up from its grandparents only a few proverbial expressions and snippets of nursery songs.

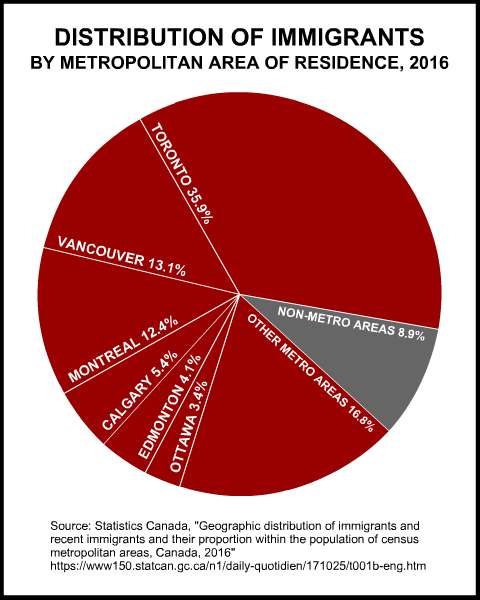

Contrast a Chinese immigrant family arriving in Vancouver in the 2010s. They arrive in a metropolis where roughly a third of the population is ethnically Chinese. Very likely they settle in a neighbourhood where Chinese are an outright majority, where their children attend schools surrounded by fellow Chinese-speakers. The community supports multiple Chinese-language newspapers and radio stations. The more popular Chinese movies are playing at the local multiplex. Chinese TV shows can be streamed online. Not only canned goods but fresh fruits and vegetables from back home are available in most grocery stores. And if in spite of all this the new arrivals get homesick, for a few thousand dollars the whole family can take a week’s vacation in China.

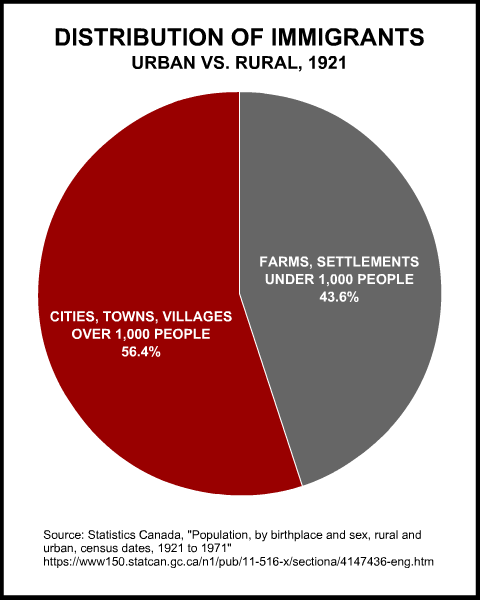

Supporters of mass immigration point out that at various times in Canada’s history, the percentage of foreign-born residents has been as high or higher than it is at present. Those earlier immigrants integrated quickly enough, so why shouldn’t these?

Source: Statistics Canada, 150 years of immigration in Canada.

But they’re overlooking the phase transition that separates a small, spread-out population from a large, densely-concentrated one. A minority of a hundred thousand people can support economic activities like newspapers, radio stations, and specialty grocery stores that a minority of a hundred can’t.

And that’s not to mention changes in trade, travel, and technology that together have reduced the pressure to integrate.

I’m not overly gloomy on Canada’s prospects in the era of mass immigration. After all, I elected to leave my small city on the prairies and relocate to hyperdiverse Vancouver, and I like it here. But it’s a matter of taste. Native-born Canadians are as entitled as newcomers to be partial to the way of life they grew up with, and it’s not crazy of them to notice that that way of life is being displaced at an ever-increasing rate.

M.

PS. I previously used the above graphs in a post this summer about high housing prices in Vancouver.

—

Update, July 28, 2020: Added book cover image and linked to Bibliography page.

0 Responses to “Phase transitions.”